The forbidden fruit of paradise? The ‘discovery’ of the coco de mer, Seychelles' treasured national symbol

Tourists holidaying in the paradise islands of the Seychelles often like to be photographed holding a giant nut or seed, the coco de mer. This double coconut, known as the coco de mer, is the national symbol of the Seychelles, and an endangered species, that successive governments have been trying to protect for over forty years.

What is this strange giant fruit? And why is it as emblematic of the Seychelles' unique flora as the Adalbara giant tortoise is of the archipelago's endangered fauna?

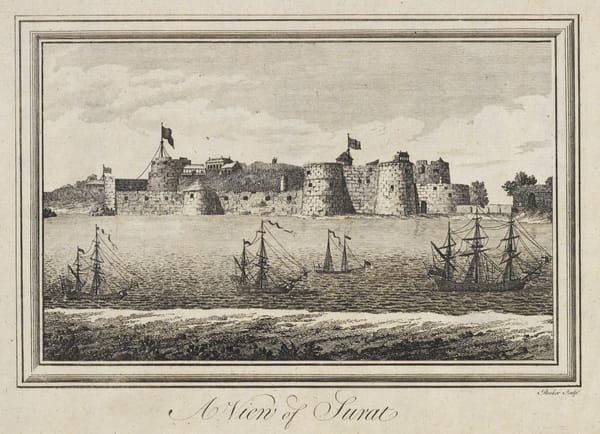

With its year-round warm tropical climate, the Seychelles archipelago of one hundred and fifty islands is home to an endemic flora, including the coco de mer, or lodoicea maldivica. The coco de mer is a giant palm that can reach over thirty metres above the ground, with fan-shaped leaves six metres long and four metres wide. Its fruit is a giant coconut, the largest fruit in the plant kingdom to date, weighing on average twenty-five kilos, but sometimes more than forty. The term coco de mer refers to both the palm tree and its fruit. Today it grows only on three islands in the Seychelles archipelago: Praslin, Silhouette and Curieuse. In fact, the coco de mer captured the imagination of European sailors and traders who sailed the waves of the Indian Ocean archipelago as early as the fifteenth century, because of its height, its gigantic leaves, but above all because of its double-shaped fruit.

We might think of the coco de mer as one of the many migrants that have crossed the Indian Ocean World since ancient times. The weight and size of the coconut meant that it was tossed about by the currents and washed up on shores thousands of miles away from the Seychelles. Before its official identification by French botanists in the eighteenth century, the coco de mer was thought to be the fruit of a distant land of plenty, magically brought to man from the mysterious region or port referred as 'Ophir' in the Old Testament from which King Salomon received gold, precious stones, diamonds and agarwood.

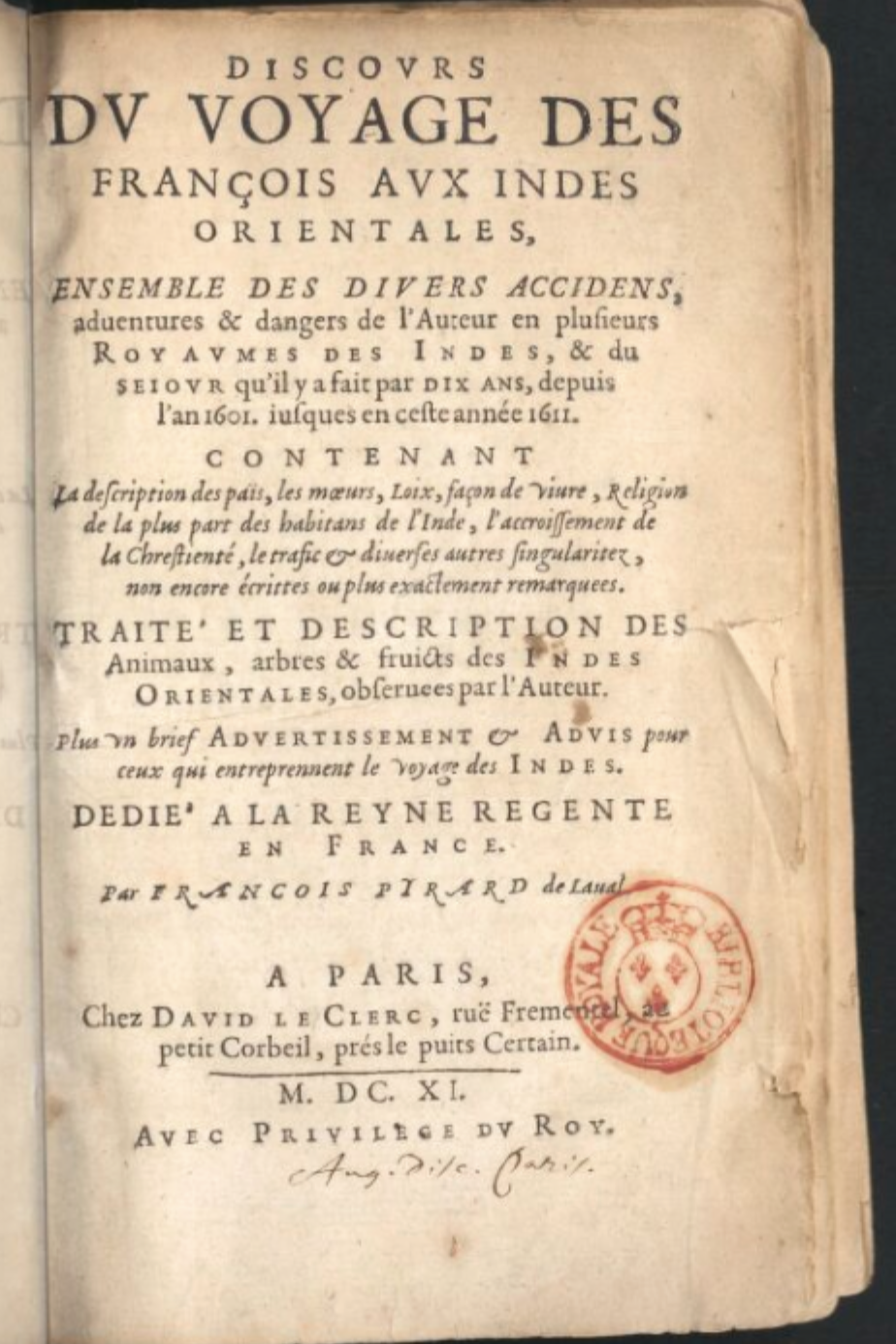

The Portuguese who found plenty of coco de mer on the shores of the Maldives believed it came from these islands. The Portuguese physician Garcia de Orta called it coco das Maldivas in his famous Colóquios dos simples e drogas da India (1563). The Portuguese missionary João dos Santos, who spent several years in Mozambique in the late sixteenth century, recalls that the giant coconut of the Maldives was found as far away as Cape Delgado. The Frenchman Pyrard de Laval who took part in an expedition from Britanny to Indonesia in the early seventeenth century and who was held captive in the Maldives for several years also mentions the giant coconut, ‘as big as a man’s head’, in his account of his time in the islands. According to Pyrard, the Portuguese called it ‘coco des Maldives’.

The coco de mer remained shrouded in mystery for many centuries. How could such a huge ‘thing’ grow? And where? According to Pyrard again, the coco de mer grew underwater, like seaweed. A contemporary of Pyrard, the French traveller Jean Mocquet who sailed from Portugal to Goa in the early seventeenth century, wrote that storms and currents brought the giant coconut to the surface and washed it ashore. For Europeans in the sixteenth and seventeenth centururies, the underwater world remained mysterious and the seabed was thought to contain many magical treasures, including the coco de mer.

Already in the sixteenth century, the coco de mer was considered a rare, precious commodity. According to Antonio Pigafetta in his account of Magellan’s voyage, the king of the Maldives regulated the trade in coco de mer. According to Pyrard, the King of the Maldives derived all his wealth from the trade in coco de mer and the one in another commodity that was also very mysterious at the time, ambergris. For the Florentine traveller Francesco Carletti, this extraordinary ‘fruit’ was harvested as a diplomatic gift harvested as a diplomatic gift, and the King of Siam received two from the King of the Maldives in the sixteenth century.

All sorts of magical and therapeutic properties were attributed to the coco de mer, from curing fever and asthma to preventing poisoning. Fragments or powder of the coconut remained extremely expensive in the markets, especially in Goa in India, until the French, according to the French botanist Bernardin de Saint Pierre, began to trade the coconut in large quantities from the Seychelles.

It was not until the second half of the 18th century, when the French began to send expeditions to explore the Seychelles archipelago from the Mascarene Islands, that the origin of the coco de mer was gradually established. A botanist who took part in Marion Dufresne's efforts to exploit the forests of Praslin noticed that many palm trees bearing the giant coconut were growing on the island. Based on the information gathered by Dufresne and his men, the French physicist Alexis-Marie de Rochon wrote the first description of the coco de mer in 1769: ‘ce bel arbre a la forme d’un grand éventail’. Two botanists and travellers, Pierre Sonnerat and Philibert Commerson, continued Rochon's work. Sonnerat left a series of drawings of the palm in his Voyage à la Nouvelle Guinée, published in 1776, while Commerson named it Lodoicea callipyge in honour of Louis XV, but also because of its erotic resemblance to a woman's bottom (callipygian in ancient Greek means ‘buttocks’).

In the early 19th century, the last commander of the Seychelles before they fell to the British in 1811, Jean-Baptiste Quéau de Quinssy, wrote a detailed description of the coco de mer.

The fact remains that the now well-identified coco de mer continued to fascinate in the late nineteenth century. The British colonial administrator Charles Gordon, who spent time in the Seychelles, wrote about the coco de mer, which he believed to be the forbidden fruit of paradise, from the Vallée de Mai, the terrestrial Eden that had finally been found.

Indicative Bibliography:

Arlette Girault-Fruet, 'Le coco de mer, premier migrant de l'Océan Indien', Carnets de recherches de l'océan indien 3, p.114-120, accessed online 16 October 2024.

Jean-Michel Filliot, 'Découvertes et botaniques: l'histoire du coco-de-mer', Etudes Ocean indien 10, (1989), p.123-130.