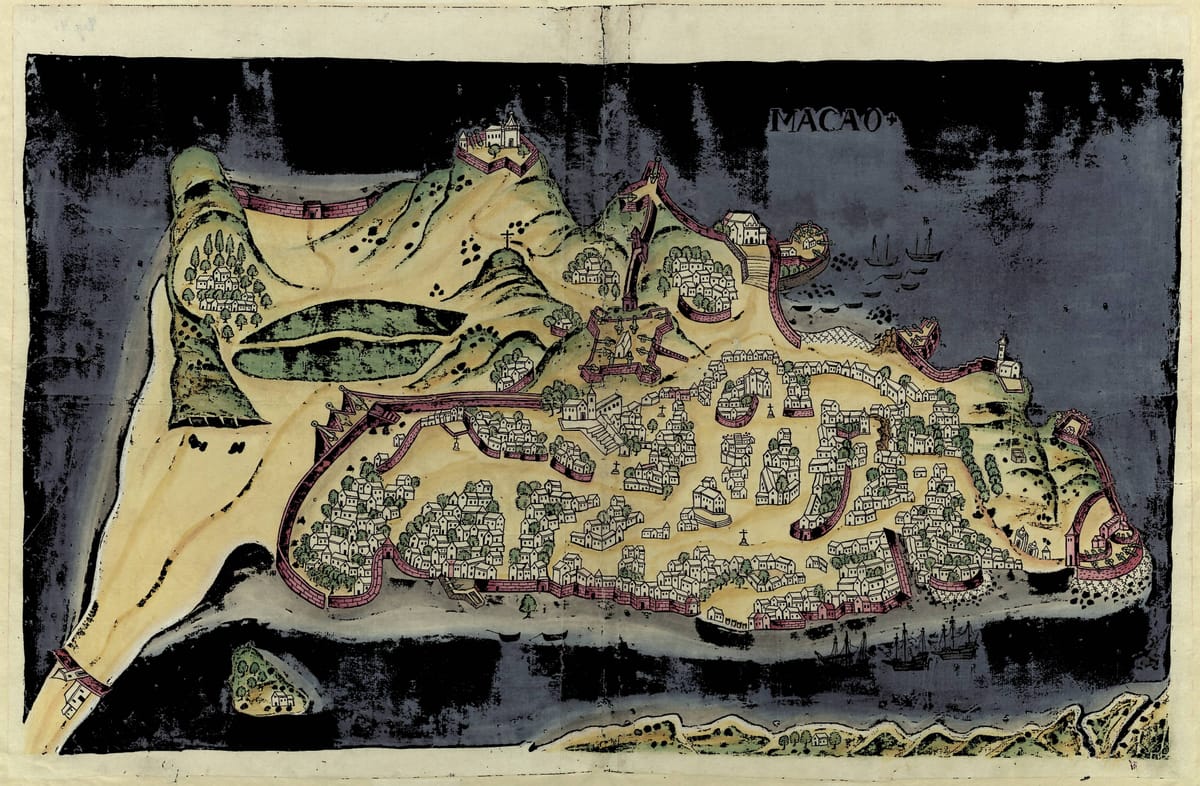

Macao

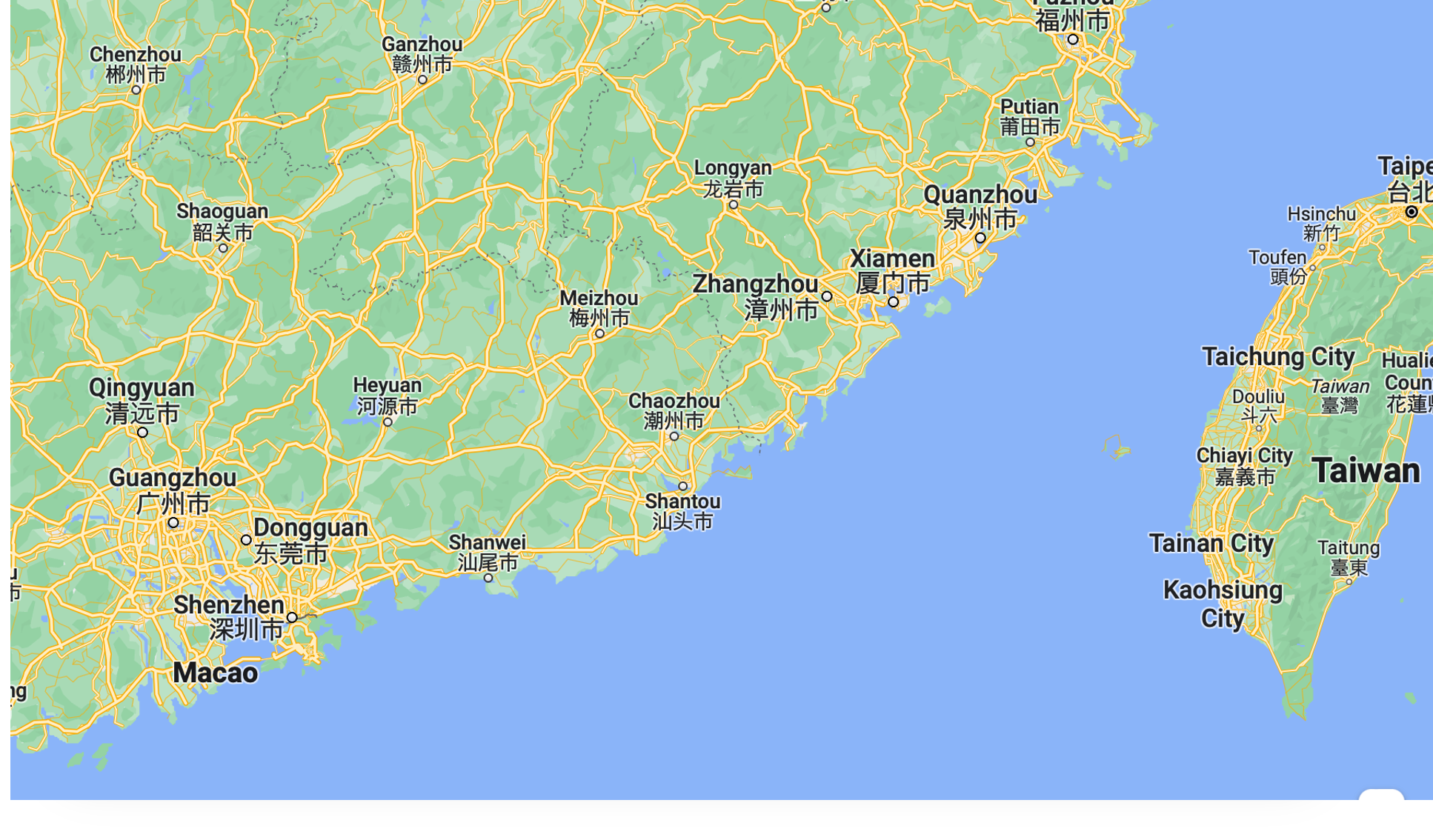

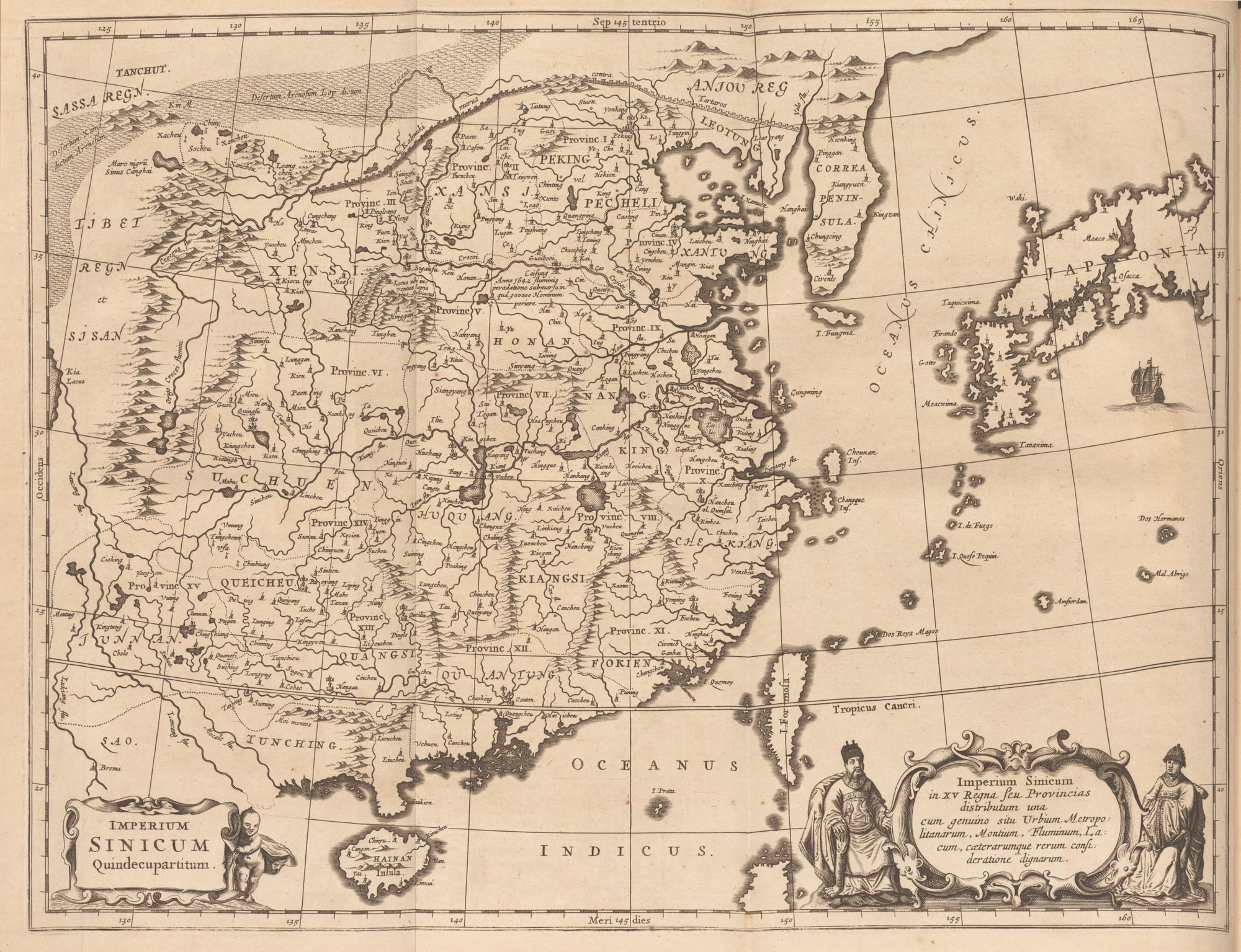

Macao is located in a peninsula in the Western Pearl River Delta by the South China Sea.

In 1557, the Portuguese were granted a permanent settlement in Macao by the Chinese court, after decades trying to establish official relations.

The status of Macao city in relation to Lisbon or the Estado da Índia was ambiguous. Although officially under the jurisdiction of the Portuguese viceroy in Goa, the senado (municipal council) enjoyed a considerable degree of autonomy. It levied import and export duties on all goods transported by Portuguese ships. The city’s wealth came mainly from trade. The Macanese elite could not invest in land because they had no hinterland. They relied on the money market and maritime trade for capital.

When the Portuguese were given permission to move to Macao, the Capitão-mor (captain-major) system had just been adopted for the voyages to Japan. In an effort to control this trade, the crown established the position of Capitão-mor of the China-Japan voyage that was conferred annually, usually by the Viceroy in Goa. Macau’s merchant community was engaged in regional commerce with other areas of South and Southeast Asia. During the Iberian Union, they also carried out private trade with Manila despite the Iberian king’s prohibition and constant admonitions.

The capitão-mor was the official representative of the Portuguese authorities vis-à-vis the Chinese and the Japanese and was also the highest judicial authority in Macao, even though he was absent for long periods due to sea voyages. After the VOC attack in 1622, the members of the Senado petitioned the Viceroy of the Estado for a military commander, the capitão-geral. The office was created, and the capitão-geral had to reside permanently in Macao and be responsible for its defence and finances.

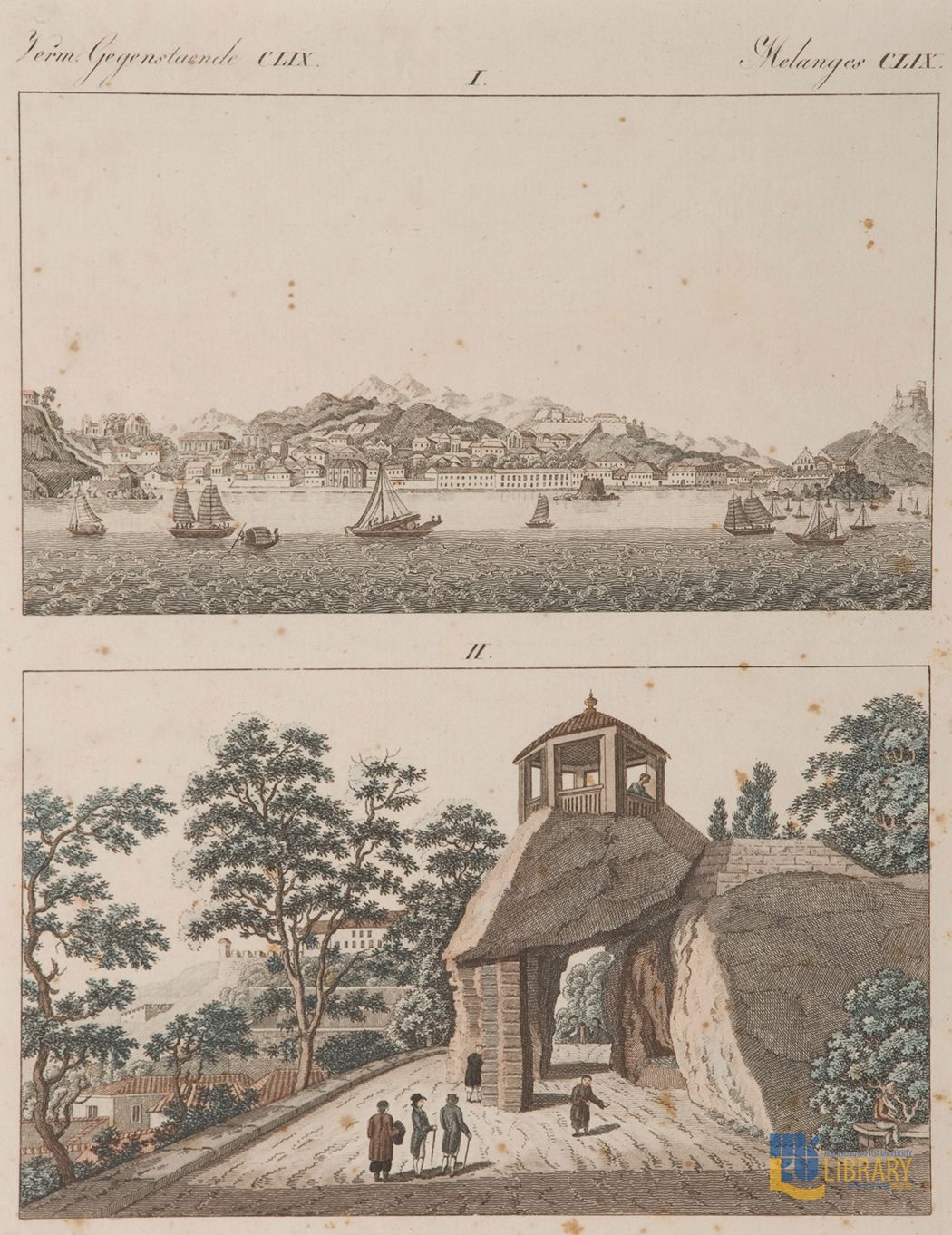

“The peace [agreement] we have with the King of China is the way he wants it to be”, wrote António Bocarro in his description of Macao to Felipe IV of Spain. The Portuguese did not own the land in Macao but had to pay rent to the Qing dynasty and customs duties on goods brought in by their ships. The Qing authorities responsible for supervising the Portuguese in Macao were in Canton, but there were mandarins located near the city walls built in 1622. The Macao dwellers were highly dependent on the Chinese authorities, who also controlled the city’s supplies.

Although Francis Xavier SJ died before the Portuguese were allowed to occupy Macao, he became the city’s patron saint. In 1576, Pope Gregorius XIII created the diocese of Macao, which included Japan and China. Macao’s Senado also contributed to the support of the Padroado and paid for the diplomatic missions sent to Beijing, Canton, Japan and the South China Sea region. In 1594, the Jesuits founded a college in the city, the colégio de São Paulo, also known as Madre de Deus. After a fire in 1835, only the façade (pictured) remained, the rest of the building having been destroyed by the flames.

Macao’s population was considerably multi-ethnic, consisting of Portuguese, Chinese and other Asians. Yet, the number of reinóis (Portuguese born in Portugal) was very small. The city’s population fluctuated throughout the year, as many of its inhabitants were absent for long periods of time due to their direct involvement in the maritime trade. Moreover, many Portuguese sailors and pilots passed through Macao in their voyages from Manila, Solor, Macassar and Cochinchina. Macao’s Christian population was overwhelmingly female, but almost none were Portuguese.

Bibliographical References

Loureiro, Rui Manuel. ‘As Origens de Macau nas Fontes Ibéricas’. Review of Culture 1 (2002): 82–99.

Oka, Mihoko. The Namban Trade: Merchants and Missionaries in 16th and 17th Century Japan. Leiden: Brill, 2021.

Sousa, Lúcio. ‘Legal and Clandestine Trade in the History of Early Macao: Captain Landeiro, the Jewish “King of the Portuguese” from Macao’. Bulletin of Kanagawa Prefectural Institute of Language and Culture Studies 2 (2013): 49–63.

Souza, George Bryan. The Survival of Empire. Portuguese Trade and Society in China and the South China Sea, 1630-1754. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Credit for the featured image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Macau_in_Livro_das_Plantas_de_Todas_as_Fortalezas.jpg