Longing for the lost Inde Francaise: Ananda Ranga Pillai, the comptoir of Pondichery and French colonial nostalgia

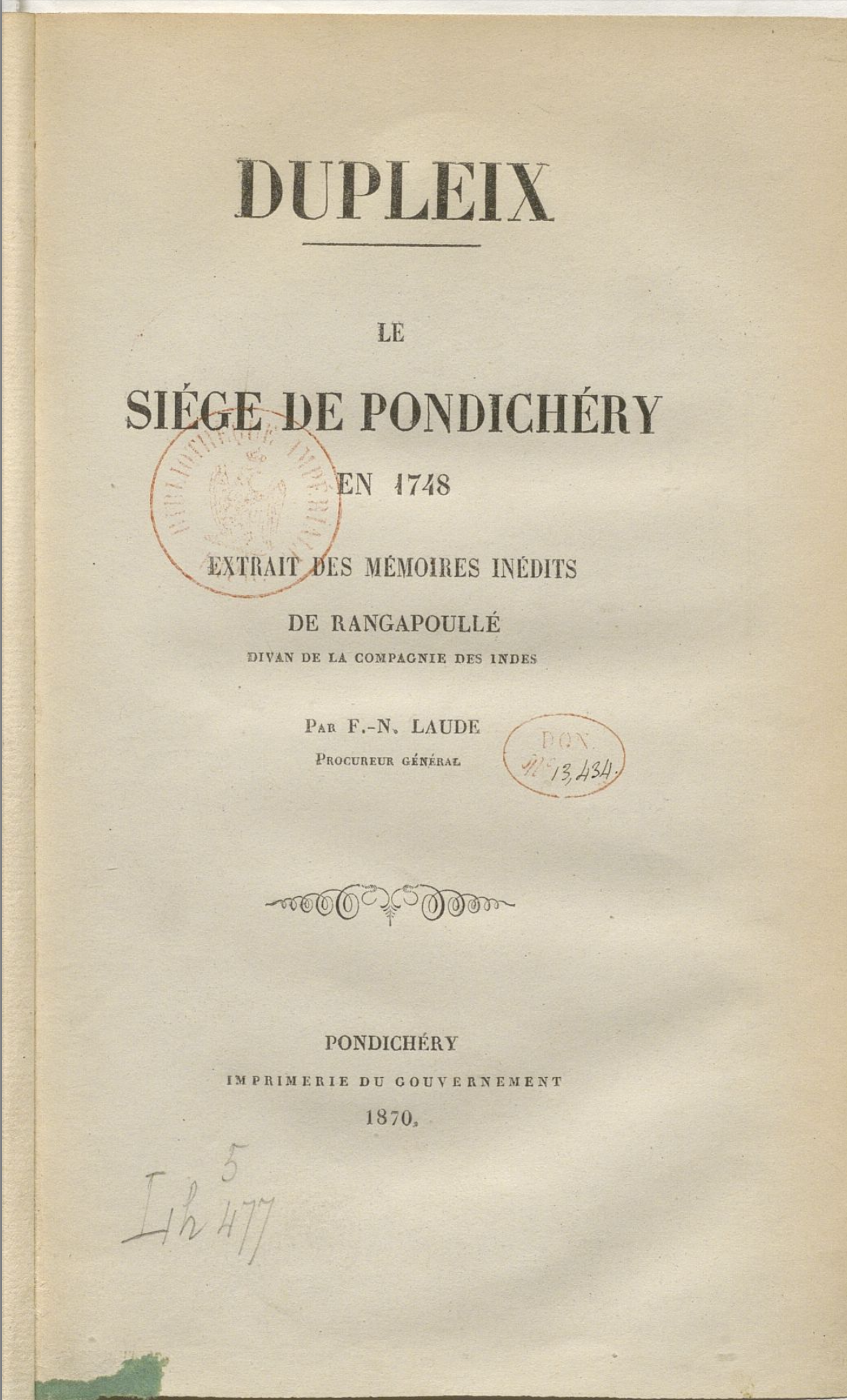

In 1870, a French colonial administrator in Pondichery, Francois-Nicolas Laude, published a brief history of the 1748 siege of the French enclave by British troops during the First Carnatic War (1740-1748), entitled Dupleix. Le Siège de Pondichéry en 1748. Extrait des Mémoires inédits de Rangapoullé, divan de la compagnie des Indes. The occasion for the publication of this book was the inauguration in Pondichery of a statue of the man who supposedly created 'French India' more than a century earlier, Joseph François Dupleix.

Interestingly, in 1870 France was at war with Prussia and was about to see Paris occupied by foreign troops and two regions on its eastern border, Alsace and Lorraine, amputated. In 1870, in the French collective psyche, France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War bore similarities to the situation in 1763, when the French crown had lost the Seven Years' War to Britain and its colonial empire had been reduced to a tenth of its pre-war size.

The loss of Alsace-Lorraine unleashed an unprecedented wave of nationalism and revanchism in France and colonial conquests abroad. The aftermath of the 1870s was a period of nostalgia and the construction of a national narrative about France and its colonial past. The two lost eastern regions of France, Alsace and Lorraine, would somehow be linked to the territories confiscated by Britain in the Treaty of Paris, from the vast expanses of Canada to Louisiana and the territories heroically conquered by Dupleix in the Caribbean. While young French pupils learnt at school that the patrie and the Alsace Lorraine were worth dying for, just like many national heroes like Vercingetorix, Jeanne d’Arc, Danton and Marat had died for the motherland, France conquered many territories in Asia and Africa. And from 1870 onward, the mission civilisatrice also became crucial to French colonialism.

Laude himself read passages from the book at the inauguration of Dupleix's statue, which still stands in Pondichery. The book consists of a long introduction and extracts about Dupleix and his actions in India from a very specific document, the contents of which are somehow misinterpreted, the 'diary' of Ananda Ranga Pillai.

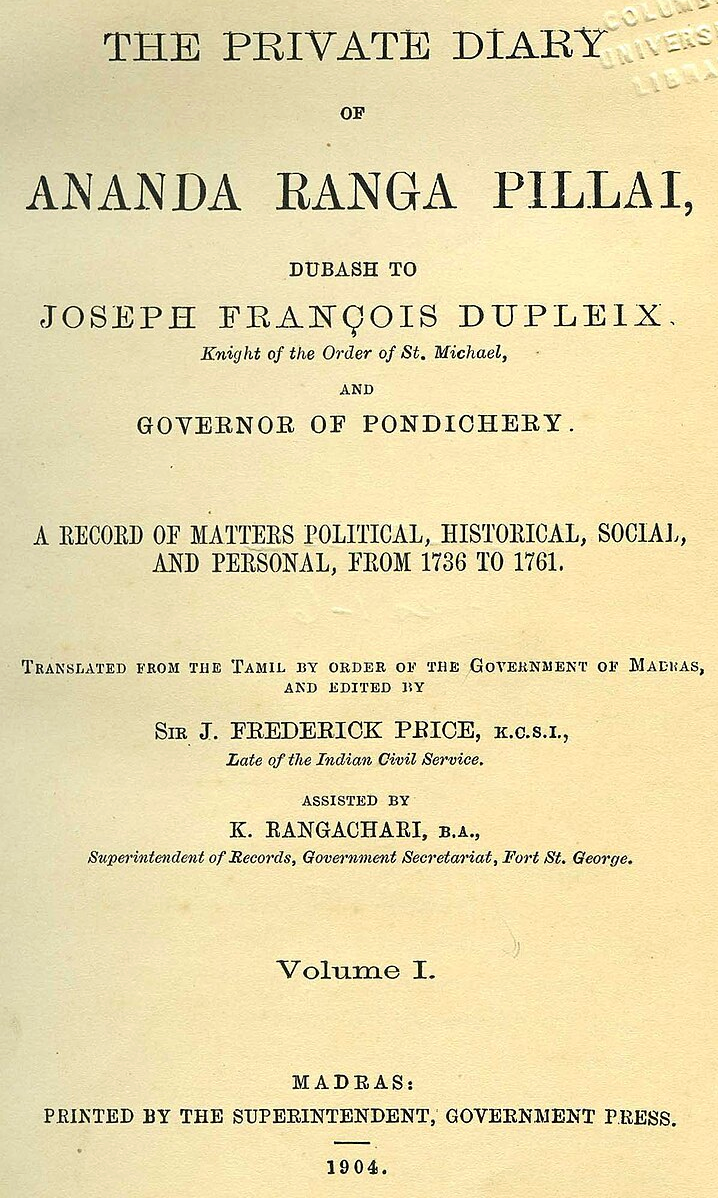

Pillai's ‘diary’ is far more than a chronicle of the commercial and political life of the French comptoir of Pondichery during a period of expansion. Rather, the twelve volumes are a history of the Carnatic Wars, in which Dupleix's strategy of forging local alliances and generating revenue through conquest in the Carnatic failed.

Parts of the diary, originally written in Tamil on palm leaves, were edited and published in France in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The only complete edition is in English and titled The Private Diary of Ananda Ranga Pillai, Dubash to Joseph-François Dupleix Knight of the Order of St Michael, and Governor of Pondichery.

Pillai's diary lived a long life, longer than that of its author, who died in 1761 at the age of fifty-two. It has been ‘rediscovered’ many times and, among other things, helped to create what Kate Marsh has called the 'myth of the Inde française'.

Who was Ananda Ranga Pillai, the author of this hybrid text?

Pillai's life is shrouded in mystery, as is the life of the document he wrote, which survived him before being rediscovered at his home in Pondichery in 1846 by Arthur Gallois-Montbrun, conseiller a la cour royale de Pondichery.

In this blog post, we are not exploring the life of Pillai's diary, whose history is inextricably linked to the history of the nineteenth century, the Oriental Renaissance and the construction of the idea of the French nation itself, but the life of the man who kept a chronicle for more than twenty-five years, between 1736 and 1760.

Ananda Ranga Pillai was born into a wealthy merchant family in Madras in 1709. Pillai gives very little information about his family, marriage and personal life in his writings.

But we do know that Pillai's father, Thiruvengada, was invited by the French to move to the French enclave of Pondichery in 1715, as part of Governor Hébert's initiative to attract merchants to the French enclave after the Peace of Ryswick, which marked the end of the Nine Years' War and saw the dawn of the so-called 'Long Peace', in order to boost trade. By 1715, a member of the Pillai family was already working as a chief courtier for the French, Nayiniyappa Pillai, whose disgrace and trial is recalled in Danna Agmon's book A Colonial Affair. It is possible that Nayiniyappa arranged for Pillai's family to move and settle in Pondichery.

Pillai's father Thiruvengada probably worked for the French for about ten years, first as a dubash and then as a chief dubash. In 1725, Pillai took over his father's business and also started working for the French. Pillai died in Pondichery during the end of the Seven Years' War in 1761, when the city was besieged by British troops. The author stopped writing when he witnessed the destruction of the city that was the symbol of what he had worked for all his life, French India.

Pillai's own son worked for the French from 1776 and lived most of his life in Pondichery. His nephew also worked for the French. And in 1791, it was his grandson's turn to enter the service of the French. Pillai's family lived in Pondichery for more than seventy-five years, serving the French East India Company.

What exactly was Pillai's role in Pondichery? Was he really the secretary, the very close 'advisor' to Dupleix that some historians have made him out to be?

Pillai's father, Pillai's uncle, Pillai himself and then his son and nephew worked for the French as dubash. The dubash or dobash were already an institution in Mughal India. They were the key to the world of pre-colonial India for the arriving Europeans, who had no understanding of the sophistication of political and economic life in Mughal India. Almost everyone who stayed in India, even for a short time, had a dubash. The dubashes were figures of mediation, with the mastery of languages as the key thing and knowledge.

Dubashes were recruited for their knowledge and extensive networks. In fact, Ananda was fluent in four languages, French, Persian, Tamil and Telugu, and, according to Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Sanskrit. So, one word could sum up what the dubash were: 'capital'. Dubashes served as moneylenders. But their social connections also ensured that Europeans could penetrate the world they had just entered. Social capital was therefore a key feature of the importance of the dubash to the Europeans.

The second half of the seventeenth century and the eighteenth century were the golden age of the dubash. They then gradually 'disappeared' with the establishment of a professional colonial administration from the beginning of the nineteenth century.

But Pillai, as we have said, would continue to exist through his diary. And he lived an interesting life in the nineteenth century, in France. While some savants in France were 'rediscovering' India and Tamil was being taught, the 'diary' was copied, partly translated, its script transformed and analysed to take a special place in the Oriental Renaissance. It was then ready to become a document illustrating a period of French history. Pillai and his diary, in which Dupleix occupies a central place, certainly helped to create the myth of the once mighty Inde Francaise briefly threatening the East India Company and the rise of the Company Raj.