Free Trade, the Abolition of Monopoly, and the Dissolution of East India Company Factories in India and Canton, 1813-1833

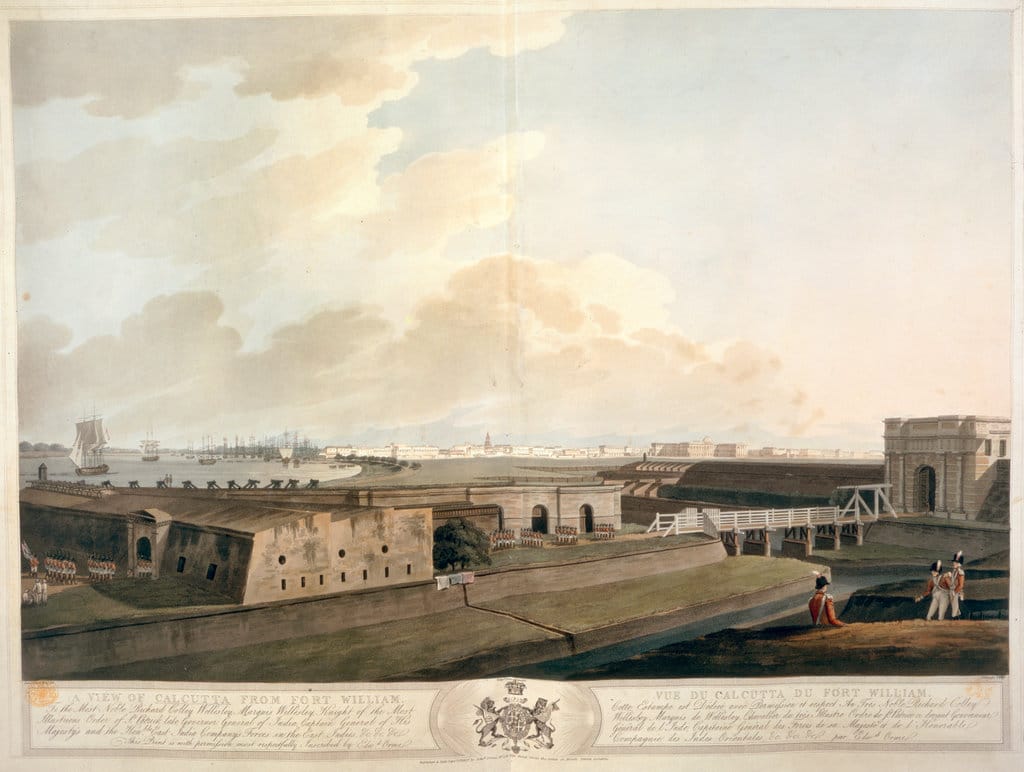

In 1813, and again in 1833, the East India Company (EIC) successfully lobbied to have its charter extended by twenty years. Yet each victory came at a heavy cost: whereas in 1813 the company lost its trading monopoly, in 1833 it forfeited all semblance of its commercial operations. While 1833 deprived the company of its original raison d’être as a commercial body, 1813 was the more momentous development, for it cleared the way for the onrush of British free trade in Asia. Behind the company’s failure to protect its monopoly lay the desire of the British government to strengthen the domestic economy amidst the pressures of war with Napoleon (Webster, “The Political Economy of Trade Liberalization”). Ending monopoly by permitting private merchants to operate in India still left much of the EIC’s functions up for contention, however. Among those questions exercising the energies of company officials and parliamentarians was what the end of monopoly meant for the company’s numerous factories in India and its single factory in Canton. Whereas in 1813 the factories were kept in place - against the wishes, as we shall see, of the domestic free trade lobby - in 1833 they were done away with altogether. Thus, ended an infrastructure of trade that the company had established piecemeal over two hundred years, ever since the first company factory was planted in India in 1613.

The persistence of the company’s India factories into the first quarter of the nineteenth century may come as a surprise. Notwithstanding the gradual, if inexorable, territorialization of the Company’s power in the subcontinent from the 1750s, factories were still a lynchpin of the EIC’s commercial structure well into the nineteenth century. By one count made in 1813, there were 52 factories still operating in India as well as several in southeast Asia (figure 1). For those eager to maintain the company’s economic hegemony in India with or without monopoly, scaremongering was resorted to in order to convince parliament that the abandonment of the factories would be disastrous. As one interviewee, Richard Waike Cox - who had spent substantial time in Bengal as a company employee - summed up matters to the parliamentary committee, the end of the factories would deprive the EIC of its ability to procure the choicest commodities, disrupt its intricate investment structures, and delay, if not wholly undermine, the efficient remittance of surplus revenue from India to Britain. Private actors using bills of exchange were considered to be insufficient to the task of performing that most crucial final function (“Richard Waike Cox, Esq,” Minutes of Evidence Taken Before the Committee of the Whole House, and the Select Committee, on the Affairs of the East India Company (House of Commons, 1813), 536-537).

In that same interview, the committee asked Cox whether, in the event the factory system was abolished and private traders did not pick up the slack, Indian weavers would be deprived of a livelihood. The committee asked:

Supposing the Company to withdraw their investment from a particular factory, and that private merchants did not enter the country for the purpose of purchasing goods for exportation, would the internal demand of the country for the goods manufactured by the weavers, be sufficient to give them employment, or would they in such case be reduced to a state of distress?

To this Cox replied:

I conceive the demand of the country would not be sufficient and that they would resort to agriculture (“Richard Waike Cox,” 540; cited in Giorgio Riello, "India and the Industrial Revolution," in Mrinalini Sinha, David Gilmartin and Prasannan Parthasarathi (eds.), The Cambridge History of the Indian Subcontinent (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming 2025).

But as if to confirm the criticisms of the free traders, Cox boasted of having 1500 weavers at his beck and call, a number that included only heads of families and not the kin who worked with them. Cox was equivocal before the committee when asked whether weavers were subjected to physical punishment when they did not deliver on orders to work with buyers other than the company. Yet Cox’s many remarks detailing the poor economic status of the weavers and the role played by native overseers in coercing deliveries from them signal just how pivotal the EIC factories were in exploiting artisanal labor in Bengal. (for more on this subject see Om Prakash, “From Negotiation to Coercion: Textile Manufacturing in India in the Eighteenth Century,” Modern Asian Studies 41/6 (2007): 1331-1368).

Figure 1 - William Milburn, Oriental Commerce, Containing a Geographical Description of the Principal Places in the East Indies, China, and Japan, with Their Produce, Manufactures, and Trade, Vol. 1 (Black, Parry, & Co. 1813), c.

Those intent on maintaining the factory status quo encountered a sustained opposition in the leadup to the 1813 legislation. The champions of free trade - intent to see the company entirely done away with - were evidently concerned that if the factories were to carry on then they would serve as vehicles for the furtherance of the EIC’s monopoly by other means. In this view, the company’s factories were regarded as mechanisms of oppression, not only against the British private trader, but also against weaving communities in regions like Bengal. Though long-winded, one contemporary tirade that made this precise argument merits quoting at length:

It is alleged, that in Bengal everything goes on smoothly, and the regulations are appealed to, in proof of the most rigid attention being paid to the interests and security of the weavers, and of the community generally; but let us look at these regulations. A commercial resident, with a large establishment of servants under him, some of them intended for coercive purposes, is placed at the head of every factory of weavers, by whom (as we have been emphatically and truly told by one of the highest and most distinguished Indian authorities) the intimation of a wish from a superior is received as a command. This alone would give the commercial resident an influence over the weavers, with which a private merchant would be quite unable to contend, whenever that influence, from whatever cause, might be turned against him; and in the rivalry and competition of trade, innumerable instances must occur to occasion it; but from the general poverty and dis tresses of these manufacturers, they are always ready to receive advances of cash from the commercial resident; and they are then, by the regulations, bound to work exclusively for the Company. When the goods of any particular factory are not, as is sometimes the case, required for the Company's investment, the resident is allowed to employ the weavers on his own private account. On these occasions, his official situation enables him to monopolize their labour and its produce. From the influence, therefore, of the resident on one hand, and the pecuniary wants of the manufacturers on the other, it is quite clear that they may be, whenever it is desired, kept in perpetual bond age to the Company's service; and when we thus see the industry of the country subject to the entire direction of the ruling authority, supported for the most part, and often irregularly, by advances from the public revenues, and all competition, the soul and essence of commerce, far removed from this delicate and feeble fabric, as if its very touch were ruin; who but the most prejudiced can possibly see or expect prosperity under such a system? It is really subversive of every principle, on which both experience and theory would teach us to found any rational hope of public good (“June 14, 1813: East India Company’s Affairs”).

Another point of discussion in the 1813 proceedings was whether to restore factories to other European powers. These had been seized during the course of the Anglo-French and Anglo-Dutch wars of the late eighteenth century and, more recently, in the protracted conflict with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. When asked whether the reopening of non-English factories were to hasten the influx of foreign traders into India, an official replied: “If the settlements belonging to the French Dutch and Danes were restored to those powers I do not conceive that the same facilities would take place in the introduction of foreigners from those settlements into the interior of the country partly because the authority of the Company's government over their own possessions has been considerably increased and because in consequence of the late treaties of alliance between the Company and the native states the residents at the courts of the native princes are enabled to exercise much more vigilant and efficient control than they were formerly enabled to do. (“Thos. Sydenham,” Lettered Minutes of Evidence on East India Affairs ... 1813, Vol. 2 (London: E. Cox & Son, 607-608.) Foreign traders in India would now have to play by the rules of the company’s game. There they would discover a commercial universe unrecognizable to their countrymen who operated there half a century before in the factories dotted all across the littorals of the subcontinent.

At the same time, even for the British free trader the company’s factory apparatus likely acted as a bulwark against commercial opportunity given their longstanding integration into the local markets. Indeed, if the evidence from 1833 is any indication, then the factories did continue to enshrine the company’s privileges against free traders. A telling indication of this comes from the motion detailing the liquidation of the company’s commercial assets:

The right of British subjects to trade with India on an entire equality with the Company cannot be denied. It cannot be pretended, that the special privileges and property belonging to the Company in that country, would operate to the exclusion of their countrymen from any essential facility of admission or trade. The dominion of the British Crown, securing equal protection for all classes of British subjects throughout Hindostan, has superseded the use and altered the character of those factories and settlements which may have been necessary to commercial dealings in former times” (“No. XI Letter from Rt. Hon. Chas. Grant, 12 Feb. 1833,” Papers Respecting the Negotiation with His Majesty's Ministers on the Subject of the East-India Company's Charter and the Government of His Majesty's Indian Territories, for a Further Term After the 22d April 1834 (J.L. Cox and Son, 1833,) 35.)

Another participant in the debate about the EIC’s future in that year further called for the company “to dispose of their factories and buildings gradually so as to avoid loss on a forced sale and to reduce their advances in order to realize the outstanding balances without unnecessary sacrifice and without distressing the parties who are under engagement to liquidate those advances by the delivery of cocoons or silk.” (“No. XXXII, Mer. Tucker’s Dissent, 30 March 1833,” Papers Respecting the Negotation with His Majesty's Ministers on the Subject of the East-India Company's Charter and the Government of His Majesty's Indian Territories... (J.L. Cox and Son, 1833, 115.) In any case, British industrialists in the 1830s had begun to lob their own salvos against the company’s factories in India. Figures like Edward Baines saw the company’s factories as not only a terminological anachronism in an age when ‘factory’ more and more connoted a mill, but also a figleaf for monopoly and a means of impoverishing the weavers (Edward Baines, History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great Britain, Vol. 1 (Fisher and Jackson, 1835), 73). Soon enough, the modern industrial factory eclipsed the early modern trading factory.

Amidst the debates about factories in India, the conversation around the factory in Canton took on a different coloring. Several of those caught up in the legislation of 1833 were keen to protect the EIC’s tea and opium monopoly and, by implication, its factory. Of course, unlike in India, the EIC had to contend with local players in the guise of the Hong merchants and the Qing administration. And private trade had flourished at Canton in various avatars from the eighteenth century onward (Paul A. Van Dyke and Susan E. Schopp eds., The Private Side of the Canton Trade, 1700-1840: Beyond the Companies (Hong Kong University Press, 2018).

In any case, the 1820s were a hard time for the company’s factory in Canton. In 1822 it had been destroyed in the great fire that swept the city. It had to be rebuilt in 1824 at the huge cost of $263,667 for land and buildings (H.B. Morse, The Chronicles of the East India Company Trading to China, Vol. IV (Routledge, 1926 [2000], 95). By the end of the decade, the company’s factory was temporarily shifted to Portuguese Macau, before returning to Canton in the early 1830s. Yet the factory was not to last. Disputes with the Qing 'viceroy' regularly flared up, including over looting of the factory and physical torture of the EIC's Chinese compradors while company factors were away in Macau. In 1833, with parliament’s passage of the act annulling the company’s commercial activities, the Canton factory was ordered closed. Only two employees of the Canton factory remained to close up shop, staying on until 1839 (William C. Hunter, The 'fan Kwae' at Canton Before Treaty Days, 1825-1844 (Kegan Paul, Trench, and Co., 1882), 32). By that point the First Opium War was beginning, which marked the onset of a new epoch in British imperial trade. In the age of unequal treaties factories existing on the coast at the sufferance of Asian powers were a distant paradigm.

The shuttering of the EIC's factories once and for all in 1833 marked an epochal shift in the nature of British trade in Asia. Though it took the EIC over a decade after its initial charter in 1600 to establish its first factory, factories had functioned as a lynchpin of its trading strategy from that point until well after 1800. A large proportion of the factories had, in fact, been built by the company after 1750. Rather than in any sense outliving their economic utility as institutions, what dealt the factories the death blow was political mobilization in the metropole against monopoly. As the expert opinion admitted to the record in 1813 and 1833 had clearly shown, the factories were deeply embedded in a variety of markets within India in particular. But they had become by the nineteenth century a parasitic and brutal presence, an unambiguous indication of the character of the colonial ruling disposition. In due course, free trade may have destroyed the unscrupulous monopoly that sustained the factories, but it too proved a willing partner in the saga of colonial exploitation.