Situating the European Factory in the Early Modern Bazaar

One of the most influential theorizations of the relationship between Asian and European merchant capital in the Indian Ocean is Rajat Kanta Ray’s model of the “bazaar economy” (Ray, “Asian Capital in the Age of European Domination: The Rise of the Bazaar, 1800-1914,” Modern Asian Studies 29/3 (1995), 449–554). In Ray’s telling, the bazaar economy that persisted from 1800 to 1914 comprised an indigenous money market that marked off the activities of Asian capitalists from the sphere of colonial financial systems and European firms. Ray’s model likely overstated the extent to which Asian capitalists were subordinate to European ones in the era of high colonialism and stands the risk of drawing too firm a distinction between the formal and informal economies. Nonetheless, Ray’s idea of the bazaar economy as a complex, if slightly opaque, arena of capitalist exchange in the age of high empire has remained influential. It supplies a useful means of envisioning a dynamic world of Asian entrepreneurialism and departs from the overly static models of the bazaar put forward by the likes of Clifford Geertz and others in the age of modernization theory (Projit Bihari Mukharji, “Magic of Business: Occult Forces in the Bazaar Economy,” Rethinking Markets in Modern India: Embedded Exchange and Contested Jurisdiction, Ajay Gandhi, Barbara Harriss-White, Douglas E. Haynes, Sebastian Schwecke (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020, 85).

Recently, a new riff on Ray’s model has been advanced in the guise of the ‘Persianate’ bazaar. In a brilliant special issue edited by Fahad Bishara and Nandini Chatterjee, a range of essays were devoted to elucidating the spectrum of financial instruments, contracts, and sales that underpinned bazaars from East Africa to Iran and India (Fahad Ahmad Bishara and Nandini Chatterjee, “Special Issue: The Persianate Bazaar,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 64/5-6 (Nov. 2021)). Arguably, historians have yet to consider how the early modern period - the age before European ‘domination,’ if one prefers to use Ray’s language - disrupts the dichotomies between Asian and European economic organization intrinsic to conceptualizations of the bazaar in the modern period. A question still unexplored and especially relevant to CAPASIA concerns how European ‘factories’ functioned in relation to the early modern bazaars of Asia. In particular, where did the European factories stand spatially in relation to the bazaars of Asia’s main commercial emporia?

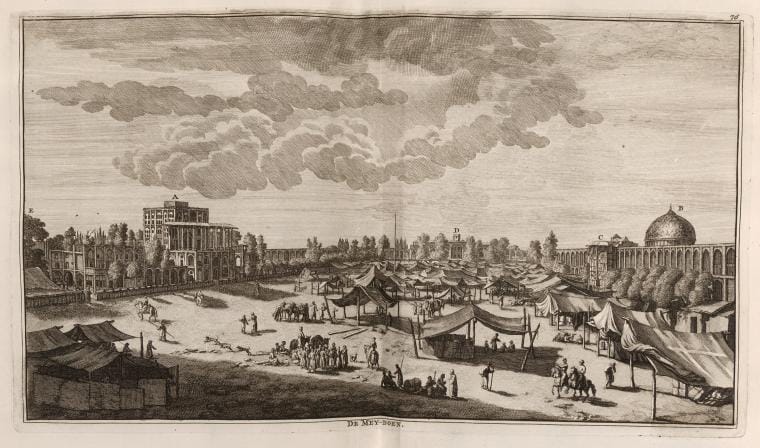

This brief essay explores this theme with reference to the Dutch and English factories constructed in Safavid Isfahan. The factories were located within the Imperial Bazaar of Isfahan (bazaar-i qaysariyyah). The ‘grand bazaar’ of Isfahan - as it is more commonly called - has been a subject of considerable fascination for architectural historians for many decades (Stephen Blake, Half the World: The Social Architecture of Safavid Isfahan, 1590-1722; Heinz Gaube and Eugene Wirth, Der Bazar von Isfahan). Depictions from the seventeenth century, such as an image from the famous travel account of Adam Olearius (c. 1637), give a sense of the magnitude of the bazaar, situated right off the famous maydan of Isfahan (figure 1). Rather than simply a commercial haven, the bazaar was a centerpiece of Safavid courtly politics and an expression of that dynasty’s penchant for monumental architecture.

An anonymous Safavid manuscript Dar danestan-i karavansarai-yi Isfahan (‘On the Knowledge of the Caravanserai of Isfahan’) from the 1660s dedicated to an analysis of the caravanserais in Isfahan, which stood adjacent to the larger complex of the bazaar, helps us situate the Dutch and English factories with ease in this dense landscape. The manuscript was published in facsimile in Der Bazar von Isfahan with a German translation (261-285) and later examined in Blake’s Half the World (117-135), where one can find English renderings of some sections. Through a survey of the multitude of caravanserais within Isfahan, the treatise demonstrates that individual caravanserais were organized on the basis of the identity of the traders and/or the commodities in which they traded. Some of these were founded by royal patrons. Stored within these cells were choice commodities from Mughal India and Ottoman Anatolia.

As for the Dutch and English, both of these were mansions given to the companies by the Shah (Blake, 132-133). Yet they were not, like many other European factories, set off apart from the hustle and bustle of the city’s economic life. The Safavid author mentions the factories at several points in the text, though only as a sideshow to what he clearly saw as the main event: the Indian, Iranian, Uzbek, and Ottoman traders in the city. In one instance he mentions that the EIC caravanserai of Mahmud Beg lay in front of the Caravansarai of Mahmud Beg (page 266-267 in the facsimile version from Der Bazar von Isfahan; Blake’s summary is 123). Instead of housing one particular kinship group, this particular caravansarai welcomes a grab bag of merchants from the Safavid cities of Qazvin, Mazandaran, Kerman, and Mashhad, as well as some Uzbek merchants from Samarqand. It did not specialize in any single commodity, and one could find there everything from porcelain vessels to musk and pepper.

Also situated in proximity to the English factory was the ‘new’ Caravanserai of the Kashanians (the inhabitants of Kashan), where gold brocade, cotton, and other items (Der Bazar von Isfahan, 282-283). Meanwhile, the Dutch factory was located in the vicinity of both the Caravanserai of Khwaja Makhram and the second Caravanserai of the Yazdians (inhabitants of Yazd). The former was named after the tutor of Shah Safi (r. 1629-1642) and specialized in, among other commodities, pomegranates, figs, and rosewater from Yazd (Der Bazar von Isfahan, 282-283). As for the latter, it carried assorted goods.

Being embedded within the bazaar was no guarantee that the VOC and EIC found Isfahan to their liking. Throughout the seventeenth century there was constant talk of abandoning Isfahan and restraining operations to Bandar Abbas (Rudolph P. Matthee, The Politics of Trade in Safavid Iran: Silk for Silver, 1600-1730, 159). Yet though they packed their bags on occasion, the companies consistently returned to Isfahan. There the factories could not dictate terms, but had to play by the complex game of the various bazaars and caravanserais. Although the companies were clearly second-string players in this framework, being embedded in the bazaar meant that the Dutch and English factors were able to obtain loans with some ease, but at considerable expense if interest rates are any indication, from Isfahan’s Indian and Iranian sarrafs.

The image of the factories nestled within the economic topography of Isfahan’s bazaar is a useful illustration of how Ray’s notion of a hierarchical bazaar economy with Europeans at the top of the food chain simply does not work for early modern Asia. If anything, the pecking order was an inversion of that which came to be in the modern era with the onset of colonialism. The question for future research will be whether similar dynamics to those on display in Isfahan existed in those sites where factories and the bazaar were spatially distinct. A provisional answer might be that, with the exception of those urban spaces where European were clear hegemons, the employees of the factories in numerous localities still had to venture out regularly from behind their protective walls and to run the gauntlet of the bazaar. This was a precondition for operating for long periods in Asia. And instead of encountering conditions of arbitrary, unpredictable, and mercurial exchange which so dominate images of the bazaar in mid-century academic scholarship, these factors were more likely to find a measure of predictability in their dealings there, if by no means impersonal and unmediated uniformity which purportedly characterizes markets that have escaped the conditions of the bazaar.